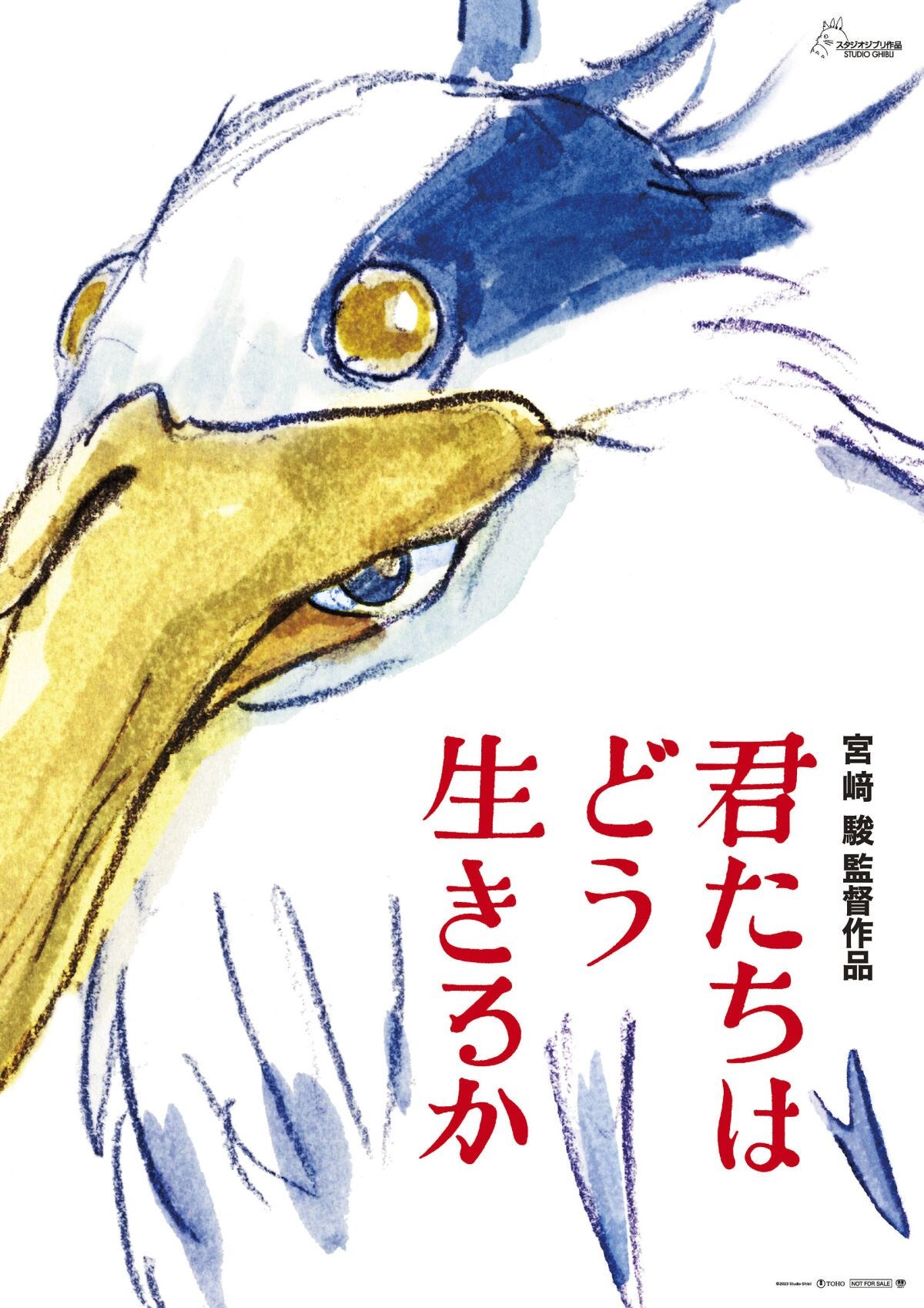

Anti Marketing: The Boy and the Heron

"A poster and a title — that’s all we got when we were children. I enjoyed trying to imagine what a movie was about, and I wanted to bring that feeling back."

Originally titled How Do You Live?, The Boy and the Heron, the highly-anticipated final film by the Japanese animation master Hayao Miyazaki, was released with nearly zero marketing support: no trailers, no plot summary, no voice cast, no still images, no TV and newspaper ads, and nothing about the film’s setting or characters.

In an interview with Japanese magazine Bungei Shunji, Studio Ghibli’s longtime lead producer Toshio Suzuki, considered Hayao Miyazaki’s right-hand man, said nothing more will be revealed about the film before it hits theatres. Toshio attributes the decision to honouring another era while hoping to spark imagination. “A poster and a title — that’s all we got when we were children. I enjoyed trying to imagine what a movie was about, and I wanted to bring that feeling back,” Toshio reportedly told Japanese broadcaster NHK. Only one piece of poster was released to accompany the release of this film, showing a sketch of a birdlike creature with white and blue feathers.

Fans of the legendary Studio Ghibli, which has long prioritised a pure experience of its works over commercial-first approaches, will recognise the decision as a very Studio Ghibli-esque move. For years, Ghibli restricted the amount of merchandise that could be licensed and made from its characters, for fear that they might become over-exposed and lose some of their magic. And when the company launched its first long-gestating theme park last year, it limited advanced media access to the park, worried that widespread coverage would make the attraction too popular, which would undercut the gentle appreciation of nature it was designed to generate for visitors.

Upon its release, The Boy and the Heron has been a massive hit in Japan, grossing 1.83 billion Yen in its opening weekend ($ 13.2 million), making it the biggest opening weekend for any Studio Ghibli film, beating out previous record holder Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). After one month of release, the number of viewers was reported as 4.12 million and the Japan box office revenue exceeded 6.235 billion Yen ($ 43.01 million).

At a time when the international film industry is floundering in a manic storm of unfeasible cost-to-box-office ratios, cinema audiences yet to return to pre-Covid levels, and striking writers and actors, the real lesson of the quiet success of The Boy and the Heron might be that a unique vision such as Hayao Miyazaki’s offers unique solutions. The enormous success of anime in general, and its own ardent following in particular, gave Studio Ghibli the bespoke option of excising marketing costs, which normally amount to as much as 50% of a film’s budget.